In this, the fourth article in my series on brownfields, I present various aspects of a completed brownfields project.

THE PROJECT

Bowery Residents’ Committee (BRC), a nonprofit organization which provides services and housing to thousands of New York City residents each year, selected a property in the University Heights section of the Bronx for its next construction project. The proposed nine-story building, to be known as “Reaching New Heights Shelter at Landing Road,” was an innovative hybrid project with two separate components: 135 studio, one-bedroom and two-bedroom rental units for formerly homeless individuals and low-income families, and 200 shelter beds for homeless, single men. When BRC began its due diligence process in 2014, the property was an asphalt-paved parking lot (see Figure 1).

PROJECT FINANCING

This project was the first one financed using the “HomeStretch” model, in which surplus revenue from the shelter portion of the project would be used to cross-subsidize the affordable housing portion of the project. New York City would fund the project at the same rate, and with the same funding, that it uses to support all organizations operating shelters. However, while a private property developer might profit from the rent paid by the city to lease shelter space, BRC reinvested any surplus into subsidies for extremely low-income housing at the project. Because the new building would have two parts, its financing was separated into two buckets, with 69% going to affordable housing construction and 31% going to the shelter construction.

To get the project started, the New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) provided a $1.2 million start-up grant to BRC. Various public agencies and non-profit corporations whose missions address affordable housing and private sector banks provided funding through tax-exempt bonds and Low-Income Housing Tax Credits to the residential portion of the project. Similarly, various public agencies, including the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the lead agency for the project, the New York City Housing Development Corporation (HDC), as well as non-profit corporations whose missions address homelessness provided funding to the homeless shelter portion of the project. The total project development cost was $65.8 million.

Permanent financing for the shelter was provided by a private pension fund through the Community Preservation Corporation (CPC). Permanent financing to the residential component was provided by a commercial bank as well as loans from HPD, HDC and the New York State Homeless Housing and Assistance Program (HHAP). In addition, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) provided funds for the installation of environmentally-friendly features, including an array of roof-mounted solar panels.

PRE-CONSTRUCTION TASKS

The money from the start-up grant funded several activities that were needed to assess the feasibility of the proposed project. Real estate professionals negotiated the property transaction; HPD, as the lead agency, was brought into the development process early; BRC met with community groups and other stakeholders to get their buy-in on the proposed project; a geotechnical survey was performed; an architect designed the building construction and prepared construction specifications that were put out to bid, resulting in the selection of a general contractor; financing of the construction phase of the project was arranged.

Several environmental tasks were required prior to construction. First, GZA GeoEnvironmental, Inc. (GZA) performed a Phase I Environmental Site Assessment (ESA), a vapor encroachment assessment, a geophysical survey, and a Phase II ESA, in which soil, soil vapor, and groundwater samples were collected and analyzed for various parameters. Most of the soil samples contained various targeted compounds at concentrations above their most restrictive standards. The soil vapor samples contained several volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at concentrations above acceptable limits. No contamination was encountered in the groundwater samples.

Based on its history and zoning actions in the area, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) had flagged the property with environmental restrictions (called an “E-designation”). As a consequence of DCP’s zoning action, properties with E-designations have environmental requirements (i.e. related to air, noise, and hazardous materials) that must be investigated before an owner can obtain a building permit from the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB). The E-designation program is managed by the Office of Environmental Remediation (OER) in coordination with DOB and DCP.

Because of the property’s E-designation, BRC had to enter New York City’s Voluntary Cleanup Program (VCP) to remediate the Site. Under the VCP, GZA addressed the requirements of the E-designation by preparing and subsequently implementing an OER-approved Remedial Action Workplan (RAWP). The RAWP included mitigation measures for the protection of workers and future occupants of the Site, including the design of a vapor barrier and sub-slab depressurization system (SSDS) for the new building and the preparation and implementation of a Community Air Monitoring Program (CAMP), which established perimeter air monitoring protocols during soil disturbance.

The project also went through an environmental assessment (EA) process called a City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) as a consequence of the various public agencies’ funding of the project. Like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), its federal equivalent, CEQR considers potential impacts of the proposed project on the environment. It evaluates the project’s impact on the physical environment, such as the area’s physiography, water supply, surface water; the project’s potential impact on other environmental factors, such as air quality and noise; as well as its potential impact on cultural resources, transportation, and the socioeconomics of the project area.

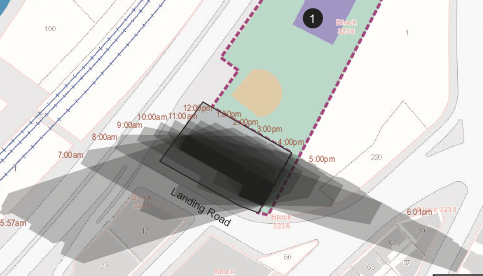

CEQR focuses on other environmental issues, including the potential impact of the building’s shadows on sensitive receptors. To explore this issue, a Tier I shadow evaluation was conducted. It determined that the proposed building was close enough to a nearby sensitive receptor, namely a public park, to warrant further study. The subsequent study utilized specialized software to model the length of the shadows on five designated days of the year. The modeling demonstrated that the shadows expected to be cast by the proposed building would only minimally impact the park to the north of the property (Figure 2 shows the expected extent of shadows cast by the building on June 21). Therefore, it was determined that shadows cast by the proposed building would be acceptable and the project was allowed to move forward unchanged.

CONSTRUCTION AND COMPLETION

The contractor broke ground in August 2015 and excavated more than 14,000 tons of contaminated soils over a five-month period. GZA conducted perimeter air monitoring during this period, in accordance with CAMP requirements. Complicating the soil removal was the discovery of an area of petroleum contamination. The spill was reported to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the contaminated soils were excavated. After acceptable post-excavation soil samples were obtained, GZA submitted Remedial Action Report to the NYSDEC, which subsequently closed the spill case.

A professional engineer licensed in New York State oversaw the installation of the vapor barrier and the SSDS, performing inspections during critical stages in their installation. Once the SSDS was activated and determined operative, GZA prepared a Remedial Action Closure (RAC) report and submitted it to OER. In January 2018, OER issued a Notice of Satisfaction to the Bronx Borough Commissioner, which notified the New York City Department of Buildings, which in turn issued a Certificate of Occupancy to BRC. The building was fully occupied by July 2018.

SUMMARY

It took four years to take this project from conception to occupancy. Due to the success of this project, hundreds of previously underserved people now live in comfort and safety. While each brownfield redevelopment project is unique, each has this in common: an underutilized parcel of land is now productive thanks to the expertise and resources provided by numerous professionals, contractors, and an array of local and state public agencies.

RECOGNITION

This project has received several awards, including Excellence in Affordable Housing Development from Urban Land Institute New York; the Andrew J. Thompson Pioneer in Housing Award from the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects; a Design Award of Merit in the Multi- Family Residential: Affordable Housing category from the Society of American Registered Architects; and the 2019 Big Apple Brownfield Award for Supportive/Affordable Housing from the New York City Brownfields Partnership (NYCBP).

Americas

Americas Europe

Europe Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español Benjamin Alter

Benjamin Alter